Japan’s Untold WWII Tragedy of “Titanic” Proportions

On August 22, 1944, at the height of World War II in the Pacific, the Japanese tramp steamer Tsushima Maru sailed out of the port of Naha, Okinawa, a 1,000 miles south of Tokyo, with a precious cargo of non-combatant civilians bound for a “safe haven” in the heartland of Japan.

Throughout the South Pacific, fierce battles were raging on land and at sea…Guadalcanal, the Marianas and Iwo Jima. The Tojo-led Japanese military machine was in retreat, but determined to fight to the very last man with its indomitable, time-honored samurai spirit laced with classic kamikaze suicide fervor.

But then a mercy ship was dispatched by the Japanese authorities to evacuate the youngest and oldest members Okinawa’s native civilian population off their home island prior to the forthcoming U.S. invasion. The Battle for Okinawa would become the final and deadliest campaign of World War II.

More than 1,600 islanders were now aboard the 6,745-ton merchant ship on their voyage to safety. But just 28 hours later at sea, more than 1,500 aboard would descend into a watery mass grave in the dark of night within 12 minutes after being hit by three torpedoes from an American submarine, the USS Bowfin.

Thus the tragic toll of the Tsushima Maru was comparable to that of the famed SS Titanic known worldwide from best-selling books and Hollywood movies ever since it sank in 1912. The Titanic’s toll was 1,513 lost with more than 700 saved. The Tsushima Maru’s: more than 1,500 lost, just 177 saved.

The sunken vessel with its entombed victims now sits in such a forbiddingly deep ocean trench it can never be retrieved. Whereas the world immediately learned of the Titanic tragedy, no one in Japan was aware of the Tsushima Maru catastrophe, for all mention of the incident was immediately suppressed by the Japanese wartime authorities.

Survivors including crew were prohibited from revealing the tragedy under threat of severe punishment. Besides, no official inquiry was ever launched and the fate of the passengers: dead or alive were never revealed to their families. It was only in the 1950s that the disaster was brought to light in Japan and the long sorrow of silence broken.

On the American side too, it took more than a decade for the crew of Bowfin submarine and the American public to learn of the Tsushima Maru’s horrific loss, especially of the 767 children aboard.

Just 59 children did survive, less than one in ten. One of these was pretty, bright-eyed 13-year-old Tsuneko Maria Miyagi, but it took a high order of courage and heroism for her to make it through to rescue.

Blown overboard and wounded by the initial torpedo explosions, she would spend four nights and three days submersed in the ocean with only her head and shoulders above water clinging to debris from the doomed ship.

Initially she was one of about 25 survivors clinging to a large piece of floating debris. Tragically, by the time of her rescue only four had survived.

With bleeding wounds to her head and body, the teen’s heroics began early in her ordeal. She recalled in the wee hours of her first night adrift at sea, she felt something submerged brush her legs. She was terrified it was a shark for the waters were teeming with them; attacking and killing survivors at will.

However, Tsuneko took a chance and reached down to catch hold of the arm of a small child, not knowing if the youngster was dead or alive or even a whole being. But her courage paid off as she brought to the surface a four-year-old boy, waterlogged but still alive, and placed him atop the floating debris to which she was clinging.

Sixty years later, to the very day in 2004, Tsuneko and the boy she rescued, Hisashi Teruya, were reunited in Naha, Okinawa during the opening ceremonies of the Tsushima Maru Memorial Hall and Museum.

Along with Hisashi were 14 members of his family spanning three generations. A photo was arranged to be taken of his family along with Tsuneko. Later, I as the photographer pondered the group photo, it hit me that if it were not for the teenager’s heroism four decades earlier, the picture would just be a portrait of Tsuneko herself alone.

By Day Three of Tsuneko’s 1944 ordeal adrift at sea, hope was turning to despair for the dwindling numbers of her fellow survivors. But as darkness fell, a vision of redemption and hope suddenly appeared through the lens of her Christian faith for the weary believer. Walking on the water she saw a bright and shining figure approaching. “I couldn’t recognize exactly who,” she said, “Jesus or the Virgin Mary or God Almighty. But just the same I understood it was the promise of hope that God was still with us.”

By noon the next day, Tsuneko’s vision did come true as a Japanese patrol boat sighted and rescued the teen of faith and her four companion survivors.

However Tsuneko’s wartime ordeals were not yet over. After a month of rest and recuperation on the island of Kyushu, the original destination of the ill-fated vessel, she was sent in harm’s way again to labor in an aircraft factory near Tokyo where kamikaze suicide bombers were being built.

Both the factory and her residence were eventually destroyed in air raids, but again she rode out the wartime storm of adversity, this time on land: the ultimate survivor.

Prior to the opening of the Tsushima Maru Memorial Hall and Museum in Okinawa in 2004, she published a book of her ordeal at sea. A poem she composed, Tsushima Maru Requiem, was set to music and played during the opening ceremonies.

And a 1,000-voice choir sang her composition as well nationally on NHK, Japan’s national television and radio broadcasting network.

The inaugural ceremonies of the new Memorial Hall ended with the presentation of a Peace Poster created by American Sunday School children from a California church. It was Tsuneko’s church as well as her husband of 52 years, the author of this account.

Author’s Note: In 2000, fate brought Tsuneko together at sea with Junichiro Koizumi, one of Japan’s most popular postwar prime ministers during the final sail-over ceremonies of the ill-fated vessel with its victims still entombed at the bottom a deep, unreachable ocean trench.

Then on September 21, 2008, Tsuneko was invited to Tokyo for a private audience with the Emperor and Empress of Japan. What was originally scheduled as a 30-minute visit lasted one and a half hours.

Her connection with the Imperial Family goes back to the days when her uncle, Professor Eisho Miyagi was tutor to the then Crown Prince Akihito, now Japan’s Emperor. After WWII, another uncle, Seisaku Ota, served as governor of Okinawa.

With his deep interest in Okinawa, the Japanese Emperor composed a Japanese waka poem based on the Tsushima Maru tragedy for his annual Year-End Presentation to the Japanese people in 1997.

Then in 2014, on the 70th anniversary of the WWII maritime tragedy, Tsuneko again met the Emperor and Empress of Japan in Okinawa to be honored as the oldest living survivor of the Tsushima Maru.

- Survivor–heroine Tsuneko and doomed ship display.

- Entrance sign: Pearl Harbor, Hawaii outdoor museum.

- Bowfin today, now a Pearl Harbor floating museum.

- Classic Okinawan musicians, 2004 opening of Tsushima Maru Memorial Hall.

- Opening ceremony Tsushima Maru Memorial Hall.

- Opening prayers, inauguration of Tsushima Maru Memorial Hall.

- Heroine Tsuneko at Tsushima Maru Memorial Hall opening ceremonies.

- Tsuneko’s American husband addresses inaugural audience.

- Masakatsu Takara, President of Tsushima Maru Memorial Foundation, also a child survivor.

- Uniformed schoolgirls view museum display.

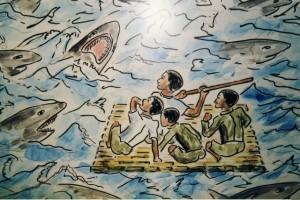

- Terror at sea for Tsushima Maru survivors.

- Tragic flashback for survivor Tsuneko.

- 2004 Reunion of Tsuneko and 4-year-old boy she saved at sea in 1944.

- Extended family of child survivor Hisashi Teruya and 14 family members and Tsuneko.

- “Survivors Three”: Tsuneko, her sister Keiko and Hisashi at museum opening.

- Prolific writer Tsuneko, author of “Tsushima Maru Requiem.”

- Cover, Tsuneko’s “Tsushima Maru Requiem.”

- “Peace & Love” poster made by California Sunday School children.

- Tsuneko at sea with Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi.

- Japan’s Imperial Palace where Tsuneko was invited to meet the Emperor and Empress in 2008.

- Tsuneko and her husband of 55 years, photojournalist Dave Bartruff.